Productivity Paradox by Pictures

I've always been intrigued by the Productivity Paradox, which refers to the slowdown in productivity growth since the 1970s despite accelerating achievements in Computer Science. Put another way, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics." - Robert Solow, a Nobel laureate in economics.

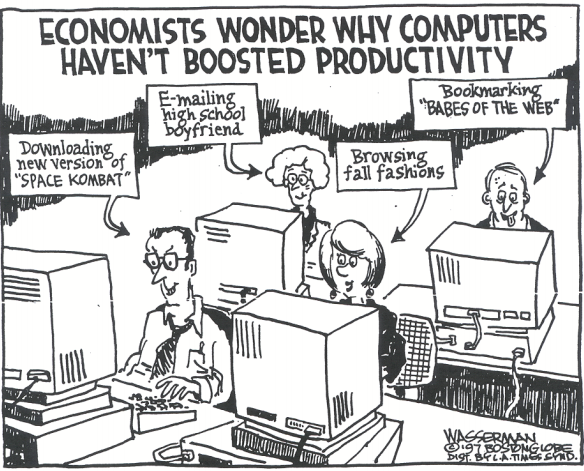

Below, I have accumulated a compilation of diagrams explaining some aspects of the Productivity Paradox, but before we go there, I thought I'd give you my two cents. I'm no economist, but the significance of the Productivity Paradox doesn't pass the sniff test. Maybe technology innovation counts for more than just more output per effort. Information at your fingertips has gotta be worth something. Anywhere communication and navigation have gotta be worth something. Weather forecasting and climate research have got to be worth something. iPad babysitting has gotta be worth something. ;-)

Ok, now that I'm on a roll, on the one hand, economist posit that we're not getting enough productivity out of our technology, but on the other hand, pundits worry that technology will replace all our jobs. BTW, I find the latter almost comical. Technology achievements have been replacing jobs since the printing press! Why are people so alarmed by it now?

Goldman Sachs Interview with Robert Gordon[*]

Robert Gordon: For the total economy, productivity growth was 2.7% from 1920 to 1970, 1.6% from 1970 to 1994, 2.3% from 1994 to 2004 during what we call the dotcom era, and just 1.0% from 2004 to the second quarter of 2015. So the productivity growth of the last 11 years was not only slower than in the dotcom era, but even slower than in the so-called slowdown period beginning in the early 1970s. The reason for the slowdown after 1970 is straightforward: we simply exhausted the productivity benefits of prior innovations [e.g. electricity, internal combustion engine, communications]... We have also now run through the payoffs of the digital revolution that followed...

The Economist's Skepticism of Innovation Pessimism[*]

Robert Gordon "muses that the past two centuries of economic growth might actually amount to just “one big wave” of dramatic change rather than a new era of uninterrupted progress..."

Chad Syverson of the University of Chicago points out that productivity growth during the age of electrification was lumpy. Growth was slow during a period of important electrical innovations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries; then it surged. The information-age trajectory looks pretty similar.[*]

Productivity Growth - Manufacturing vs All Sectors

When thinking about manufacturing’s declining share of the economy, it’s easy to think there must be something wrong with the manufacturing sector. But the truth is closer to the opposite: Manufacturing industries are victims of their own success. In recent decades, the manufacturing sector has consistently enjoyed higher productivity growth than the economy as a whole. Manufacturing is shrinking relative to the broader economy precisely because it has continued to get more productive even as demand for manufactured goods plateaued. That’s the productivity paradox.[*]